“Closet”-Shaming is for Haters

Content warning: this post contains a short description of an anti-gay hate crime.

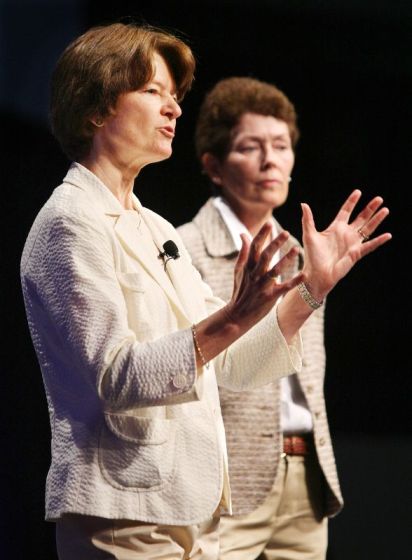

Sally Ride (left) and partner Tam O’Shaughnessy (right) address the ALA. (Image Credit: ALA.)

Let’s go back in time, shall we?

I know. It seems preposterous, on the Internet, to go back even a few weeks. I’m hoping you’ll feel like humoring me.

Let’s go back to July 2nd, to the Andrew Sullivan piece, in which Anderson Cooper self-identified as gay. Then let’s come forward, to just three weeks ago: to July 23rd and the untimely death of Sally Ride. In the wake of Ride’s death, the public became aware for the first time, of her 27-year partnership with psychologist Tam O’Shaughnessy. Both Cooper’s public declaration and Ride’s posthumous outing revived our cultural conversations about the closet. Or, at least, they revived our conversations about the closeted. As I mull over the public response to these two stories, I’m aware — once more — of the importance of that distinction.

In response to the news of Ride’s same-sex partnership, LGBT organizations largely embraced her as the newest entry into a Who’s Who of queer heroes. Regardless of how Ride felt about the label “lesbian,” we have now affixed that title to her memory, permanently. We’ve also affixed the awareness that she never offered this information to the public while alive. In short, she — like Anderson Cooper — was (somewhat)* closeted.

The reaction from LGBT figureheads to Ride’s lifelong reticence about her sexuality – has ranged, so far, from c’est-la-vie shrugs to shaken fingers. Organizations like the HRC have vocalized an attitude that’s effectively “it would have been nice, but we’ll take what we can get.” Others — among them, columnist Andrew Sullivan — have been less sympathetic. A single day after Ride’s death, Sullivan termed her “the absent heroine,” the lesbian role model who could have been, but wasn’t. Ride, in Sullivan’s view, prioritized her own privacy over the message of hope she might have spread to young queer scientists across the globe. Sullivan’s critiques echo the logic of the Anderson Cooper e-mail he shared in July: “Visibility is important, more important than preserving […] privacy.” From this perspective, the discomfort of the individual around “coming out” pales in comparison to the need for representation.

For those in the Sullivan school of thought, claims of privacy have become increasingly unacceptable. The fact that, legally, it was “privacy” that paved the way for gay rights increasingly fails to hold water, in a queer community where “the right to privacy” so often functions as “don’t ask, don’t tell” — where, in short, privacy means invisibility and invisibility means erasure. In this context, queer celebrities need a far better excuse than “privacy” for staying closeted. Or – better yet – they need to just come out.

Of course, not everyone subscribes to Sullivan’s perspective – or to the HRC’s. The Web is rife with the suggestion that coming out quietly, almost as an afterthought, suggests progress. (This post, from evolutionary biologist Jerry A. Coyne, is one example.) If profiles of Ride have minimally commented on her relationship, goes the argument, it is only because lesbianism has become so acceptable that it no longer warrants any special note. Essentially, we gays feel no more need to draw attention to our orientation than our straight counterparts do to broadcast their own. Queerness is now so mainstream, it’s not worth mentioning.

This is, not surprisingly, an argument being made primarily by straight people.

Claims like Coyne’s, that obituaries and wedding announcements rarely mention homosexuality because we now live in a country where “it’s no big deal,” are not easy for the rest of us to swallow. Not when we remember the teenage lesbian couple shot, execution-style, in Texas this past June. Not when we’re still consistently treated as objects of entertainment or objects of disgust. Not when the right of sepulcher so rarely applies to same-sex partners, when only 6 states recognize our marriages, when we can so easily lose custody of our children. Not yet.

Ride’s gay identity is not irrelevant. We have not passed the point of needing openly gay heroes. We have not assimilated so fully into straight America that our representation is unnecessary.

Still, I struggle to swallow Sullivan’s reprise of the old Harvey Milk edict, “come out, come out wherever you are.” I struggle with queer rights activists who position the closeted as opponents of gay rights. Who ignore the dangers of coming out in so many households, neighborhoods, and subcultures. Who dismiss those dangers as necessary risks.

Gay-on-gay pressure to come out is the “bootstraps” of queer discourse: “It wasn’t easy for me, but I did it anyway. Now, why can’t you?”

Yet, how often do we take issue with straight public figures for not dismantling the closet? Who’s asked NASA to ensure future queer astronauts have options beyond those of Sally Ride? Who’s demanded science and technology programs invest in our involvement, more broadly? Who’s holding the media accountable? Why are we still so quick to believe we have a right to other people’s private lives — and still so slow to change the public influences upon them?

It is a long known fact in social justice circles that the burden to educate and act against oppressive structures must not rest solely on the backs of the disenfranchised. It is a fact rarely put into practice, however, and here again, it’s getting lost.

Those of us who carry the burden of oppression are the most likely to recognize it exists. We are the most likely to understand how insidious it is and how wrong. We are the most likely to take action against it. But we are not the most responsible for doing so.

We have every right to live our lives privately, safely, and as we choose. Transparency is a powerful tool, but none of us is obligated to make use of it. Until we hold the privileged to the same standard for dismantling the closet, I do not believe in judging members of oppressed populations for their failure to do so.

This is the Internet. We’re meant to do better. We’re meant to move forward.

—

(*It should really be more than a footnote on this point that it’s a bit sketch to refer to two people, both out to those who knew them, as closeted because they “failed” to tell the media. Check out this Tumblr post from Stephen Ira for more on this point.)

Leave a comment